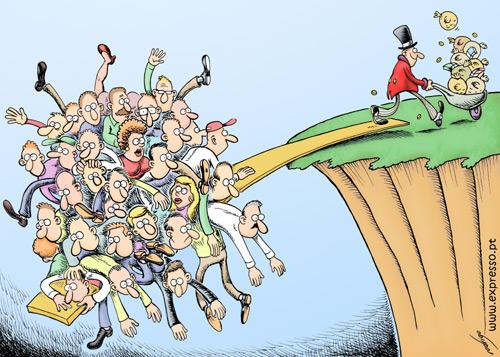

( Injustice and Inequality )

Oct 27, 2012

Current trends in energy supply and use are patently unsustainable – economically, environmentally and socially. Without decisive action, energy-related emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) will more than double by 2050 and increased oil demand will heighten concerns over the security of supplies. We can and must change our current path, but this will take an energy prevolution and low-carbon energy technologies will have a crucial role to play. Energy efficiency, many types of renewable energy, carbon capture pand storage (CCS), nuclear power and new transport technologies will all require widespread deployment if we are to reach our greenhousegas (GHG) emission goals. Every major country and sector of the economy must be involved. The task is also urgent if we are to make sure that pinvestment decisions taken now do not saddle us with sub-optimal technologies in the long term.

Oct 25, 2012

European Economic Woes Spur Separatists in Pockets of Prosperity

Can states of the "Old Continent" survive the economic crisis? Separatist movements across Europe have gained popularity during the last few months. The separatist New Flemish Alliance dominated Belgium's Dutch-speaking Flanders in the last elections; protests are held for the independence of Venice and South Tyrol in Italy; separatists remain strong in the Basque region of Spain; and respective referendums will decide the future of Catalonia and Scotland. Regions demanding autonomy are not the most affected by the crisis. On the contrary, in times of economic instability, "the separatist trend has been strongest in prosperous regions of Europe, where there is growing resentment at having to pay for the less well-off." (New York Times)

Income inequality has soared to the highest levels since the Great Depression, and the recession has done little to reverse the trend, with the top 1 percent of earners taking 93 percent of the income gains in the first full year of the recovery.

The yawning gap between the haves and the have-nots — and the political questions that gap has raised about the plight of the middle class — has given rise to anti-Wall Street sentiment and animated the presidential campaign. Now, a growing body of economic research suggests that it might mean lower levels of economic growth and slower job creation in the years ahead, as well.

“Growth becomes more fragile” in countries with high levels of inequality like the United States, said Jonathan D. Ostry of the International Monetary Fund, whose research suggests that the widening disparity since the 1980s might shorten the nation’s economic expansions by as much as a third.

Reducing inequality and bolstering growth, in the long run, might be “two sides of the same coin,” research published last year by the I.M.F. concluded.

Since the 1980s, rich households in the United States have earned a larger and larger share of overall income. The 1 percent earns about one-sixth of all income and the top 10 percent about half, according to statistics compiled by the respected economists Emmanuel Saez of the University of California, Berkeley and Thomas Piketty of the Paris School of Economics.

For years, economists have thought of such inequality in part as a side effect of policies that fostered the country’s economic dynamism — its tax preferences for investment income, for instance. And organizations like the World Bank and the I.M.F., which is based in Washington, have generally not tackled inequality in the world head on.

But economists’ thinking has changed sharply in recent years. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development this year warned about the “negative consequences” of the country’s high levels of pay inequality, and suggested an aggressive series of changes to tax and spending programs to tackle it.

The I.M.F. has cautioned the United States, too. “Some dismiss inequality and focus instead on overall growth — arguing, in effect, that a rising tide lifts all boats,” a commentary by fund economists said. “When a handful of yachts become ocean liners while the rest remain lowly canoes, something is seriously amiss.”

Income Inequality May Take Toll on Growth

Picture Credit: intelligentspeculator.net |

In this article Annie Lowrey highlights the rising share of US income going to the highest earners. She argues that income inequality has a big impact on economic growth and, quotes an IMF economist, “when a handful of yachts become liners while the rest remain lowly canoes, something is seriously amiss.” While both US presidential candidates agree that restoring the “middle class” is crucial to the economy, they disagree strongly on the policy alternatives. Outcomes of these policies will be limited if there is no solid reform to the US economic and financial system.

Sometimes we choose not to solve big technological problems.

Sometimes we fail to solve big problems because our institutions have failed.

Sometimes big problems that had seemed technological turn out not to be so, or could more plausibly be solved through other means.

Finally, sometimes big problems elude any solution because we don't really understand the problem.

What to Do

It's not true that we can't solve big problems through technology; we can. We must. But all these elements must be present: political leaders and the public must care to solve a problem, our institutions must support its solution, it must really be a technological problem, and we must understand it.

The Apollo program, which has become a metaphor for technology's capacity to solve big problems, met these criteria, but it is an irreproducible model for the future. This is not 1961: there is no galvanizing historical context akin to the Cold War, no likely politician who can heroize the difficult and dangerous, no body of engineers who yearn for the productive regimentation they had enjoyed in the military, and no popular faith in a science-fictional mythology such as exploring the solar system. Most of all, going to the moon was easy. It was only three days away. Arguably, it wasn't even solving much of a problem. We are left alone with our day, and the solutions of the future will be harder won.

We don't lack for challenges. A billion people want electricity, millions are without clean water, the climate is changing, manufacturing is inefficient, traffic snarls cities, education is a luxury, and dementia or cancer will strike almost all of us if we live long enough. In this special package of stories, we examine these problems and introduce you to the indefatigable technologists who refuse to give up trying to solve them.

To contemporaries, the Apollo program occurred in the context of a long series of technological triumphs. The first half of the century produced the assembly line and the airplane, penicillin and a vaccine for tuberculosis; in the middle years of the century, polio was on its way to being eradicated; and by 1979 smallpox would be eliminated. More, the progress seemed to possess what Alvin Toffler dubbed an "accelerative thrust" in Future Shock, published in 1970. The adjectival swagger is pardonable: for decades, technology had been increasing the maximum speed of human travel. During most of history, we could go no faster than a horse or a boat with a sail; by the First World War, automobiles and trains could propel us at more than 100 miles an hour. Every decade thereafter, cars and planes sped humans faster. By 1961, a rocket-powered X-15 had been piloted to more than 4,000 miles per hour; in 1969, the crew of Apollo 10 flew at 25,000. Wasn't it the very time to explore the galaxy—"to blow this great blue, white, green planet or to be blown from it," as Saul Bellow wrote in Mr. Sammler's Planet (also 1970)?

The great energy transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources of energy is under way. As fossil fuel prices rise, as oil insecurity deepens, and as concerns about pollution and climate instability cast a shadow over the future of coal, a new world energy economy is emerging. The old energy economy, fueled by oil, coal, and natural gas, is being replaced with an economy powered by wind, solar, and geothermal energy. The Earth’s renewable energy resources are vast and available to be tapped through visionary initiatives. Our civilization needs to embrace renewable energy on a scale and at a pace we’ve never seen before.

We inherited our current fossil fuel based world energy economy from another era. The 19th century was the century of coal, and oil took the lead during the 20th century. Today, global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2)—the principal climate-altering greenhouse gas—come largely from burning coal, oil, and natural gas. Coal, mainly used for electricity generation, accounts for 44 percent of global fossil-fuel CO2 emissions. Oil, used primarily for transportation, accounts for 36 percent. Natural gas, used for electricity and heating, accounts for the remaining 20 percent. It is time to design a carbon- and pollution-free energy economy for the 21st century.

Oct 24, 2012

Among the trends:

- Protesters around the world show a growing unwillingness to tolerate unethical decisionmaking by power elites.

- An increasingly educated and Internet-connected generation is rising up against the abuse of power.

- Food prices are rising, water tables are falling, corruption and organized crime are increasing, environmental viability for our life support is diminishing, debt and economic insecurity are increasing, climate change continues, and the gap between the rich and poor continues to widen dangerously. However, the most recent data from the World Bank shows that the share of world population living in extreme poverty has fallen from 52% in 1981 to about 20% in 2010.

- The world is in a race between implementing ever-increasing ways to improve the human condition and the seemingly ever-increasing complexity and scale of global problems.

“The world is getting richer, healthier, better educated, more peaceful, and better connected, and people are living longer; yet half the world is potentially unstable,” according to Jerome C. Glenn, CEO of The Millennium Project and co-author of the “2012 State of the Future,” an overview of our global situation, problems, solutions, and prospects for the future.

The 16th Annual Edition includes 145 pages and a 10,000 page electronic supplement with more than 1,500 additional pages of detailed current material, and searchable research from the past 16 years. It is available on CD, USB flash drive, or download.

The report is a distillation of research, including tables, graphs, and charts with special chapters on 15 Global Challenges, the State of the Future Index, changing stereotypes about women around the world over the past 50 years and projected next 50 years, future factors affecting cooperatives and businesses, and futures of ontologists.

Oct 20, 2012

In fact, this issue is just the latest incarnation of a rather old debate. Walter Lippmann famously argued that public opinion was too fickle to be a reliable guide to policy, and that better-informed elites would have to "manufacture consent" in order to lead effectively. Realists like George Kennan used to worry that democracies were no good at statecraftbecause public passions would warp the conduct of foreign policy, although other scholars have argued that democracies often out-perform authoritarian states because they are better at correcting their mistakes. Social scientists have long debated whether media coverage has any systematic effect on wartime behavior, military intervention, or other foreign policy elements.

Oct 11, 2012

Facts are being manufactured all of the time, and, as Arbesman shows, many of them turn out to be wrong. Checking each by each is how the scientific process is supposed work, i.e., experimental results need to be replicated by other researchers. How many of the findings in 845,175 articles published in 2009 and recorded in PubMed, the free online medical database, were actually replicated? Not all that many. In 2011, a disheartening study in Nature reported that a team of researchers over ten years was able to reproduce the results of only six out of 53 landmark papers in preclinical cancer research.

The field of scientometrics – the science of measuring and analyzing science – took off in 1947 when mathematician Derek J. de Solla Price was asked to store a complete set of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society temporarily in his house. He stacked them in order and he noticed that the height of the stacks fit an exponential curve. Price started to analyze all sorts of other kinds of scientific data and concluded in 1960 that scientific knowledge had been growing steadily at a rate of 4.7 percent annually since the 17th century. The upshot was that scientific data was doubling every 15 years.

Terrorism is an enduring reality. While geopolitical changes may cause a shift in the actors who employ terrorism as a tactic, terrorism will continue to be used no matter what the next geopolitical cycle brings. It is, and will continue to be, a tactic used by militant actors who want to confront a militarily superior enemy. Focusing on the tradecraft used in attacks and charting its changes and trends not only permits observers to understand what is happening and why but also provides an opportunity to forecast what is coming next.

Oct 5, 2012

A new digital revolution is coming, this time in fabrication. It draws on the same insights that led to the earlier digitizations of communication and computation, but now what is being programmed is the physical world rather than the virtual one. Digital fabrication will allow individuals to design and produce tangible objects on demand, wherever and whenever they need them. Widespread access to these technologies will challenge traditional models of business, aid, and education.

Oct 3, 2012

Urban areas around the world are expanding at twice the rate of their populations, reversing historic trends toward increased density within city limits. The result will be more loss of habitat and biodiversity, warns a team of researchers in a new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

More than 1 million square kilometers of land—largely in biodiversity “hotspots”—have a high probability of being converted to urban use by 2030, with nearly half of the expansion occurring in Asia (primarily China and India), according to the authors. However, the fastest land-to-urban conversion will occur in Africa, which will see urban land cover grow 590% above the 2000 level.

Oct 2, 2012

Lester R. Brown Presentations for Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)