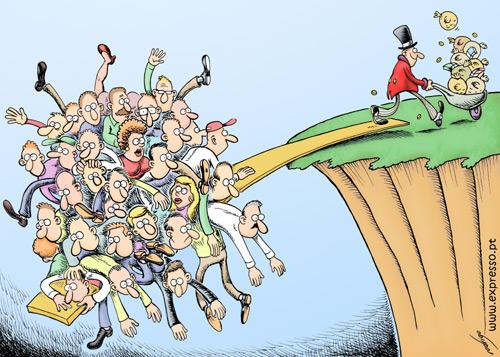

Futures studies work best when they're vague and build upon current trends to their logical (and often extreme) conclusion. Along the way, they usually play into their intended audience's hopes and fears: economic collapse, infinite growth for the middle class, Malthusian predictions of food crashes, and a belief in the fundamental know-ability of what is to come.

At the same time, any specific prediction in these texts will almost invariably be wrong. And that limits how useful they can ever be beyond a limited scope of activity. It is rare to see government officials or even corporate executives making long-term plans based on a vision of the future laid out in these studies. You just won't hear someone saying, "We should do this because of GT2030."

That doesn't mean this sort of study is useless. The GT2030 report is important for how it's changing the process and trying to encourage adaptive thinking about the future. It helps leaders understand not just the current trends (which can change on a moment's notice, in the way the 2008 recession undid all the previous predictions of forever-growth), but also how to be flexible enough to adapt to rapid change.

Leaders should look at reports like GT2030 and think about how they can evolve current institutions to be more adaptable and flexible in the future. It seems odd to think that the decentralized world GT2030 describes is going to be met with institutions that were designed in the 1940s.