Chinese Ratings Agency Threatens US with New Debt Downgrade - (Guardian - November 11, 2011)

The head of China's biggest ratings agency, Dagong Global Credit Rating, is warning that it may downgrade the US's sovereign debt rating again because of Washington's failure to tackle the federal budget deficit. Dagong, which has maintained a pessimistic outlook on US fiscal policy, has been leading the charge to downgrade US debt over the last 12 months, lowering the US rating from AA to A+ a year ago.

Nov 30, 2011

Nov 27, 2011

More specifically, the report echoes other forecasts (see CSS’s Strategic Trends 2011) in predicting a redistribution of wealth and economic power “roughly from West to East” with “no other countries projected to rise to the level of China, India or Russia” or “match their individual global clout.” Complementing this trend will be the sustained political pressures caused by economic growth and a growing competition over strategic resources, to include energy, water and food. In terms of energy, viable technological alternatives to hydrocarbons may exist by 2025, but it is questionable if the incentives to adopt them on a wide enough scale will exist by then. In turn, terrorism, though less widespread than now, will become more technologically sophisticated and dangerous. The use by terrorists groups of advanced tactical weapons will become more common and the availability of biological, radiological and chemical weapons will grow. In fact, the chances of a hostile nuclear detonation, terrorist or otherwise, “though remaining very low,” will nevertheless increase.

Unsurprisingly, the report further suggests that the big losers of 2025 will be Europe and Japan, where ageing populations and inadequate immigration policies will continue to undercut economic growth and capabilities. In the U.S., where birth rates are higher, the effect will be less severe and will most likely be offset by immigration.

Global Trends 2025 believes that the international system will become genuinely multipolar in the coming years. Although multipolar systems tend to be prone to conflict, the report argues that by 2025 the world will most likely resemble the 19thcentury, with its familiar arms races, territorial expansionism and military rivalries. This system-wide evolution, however, will not represent a simple return to the past. On the contrary, multiple actors and competing sources of political identity will make for an international order that is far more dynamic and complex than the one that led to the death of five tottering empires in 1914-1918.

Recommended Reading

“Africa: Will the Continent Break Through,” in Juggernaut: How the Rise of Developing Countries Is Reshaping the World Economy; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2011

The Futures Report 2011 ; Global Futures and Foresight, 2011

World Order in 2050 ; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2010

Will the Global Crisis Lead to Global Transformations?; Grinin, Leonid ; Korotayev, Andrey: Journal of Globalization Studies, 2010

The Global Future and Its Policy Implications: Views from Leading Thinkers of Five Continents ; Atlantic Council of the United States, 2009

The Global Future and Its Policy Implications: The Views from Johannesburg, Lagos and Cairo; Atlantic Council of the United States, 2009

Global Risks 2008 ; World Economic Forum, 2008

Strategic Challenges ; Institute for National Strategic Studies, 2008

Emerging Threats in the 21st Century - Strategic Foresight and Warning ; Center for Security Studies, 2007

The World in 2030: Regional Trends ; Il Centro Militare di Studi Strategici, 2007

Global Demography: Face, Force and Future ; World Demographic Association, 2006

Global Futures and Implications for US Basing ; Atlantic Council of the United States, 2005

Globalization and Future Architectures: Mapping the Global Future 2020 Project ; Chatham House, 2005

Mapping the Global Future ; National Intelligence Council, 2004

Both STRATFOR andStrategic Trends 2011 are convinced that the U.S. should maintain its regional influence in the short term, but the continued diversification of its energy supplies beyond the Middle East, coupled with a general decline in the threat of jihadist terrorism, might increasingly permit Washington to divert its attention to Asia Pacific, where it will confront the growing influence of China. Indeed, the United States may even divert attention to issues that are closer to home. In the case of Mexico, the United States has a near-neighbor that is, in the opinion of many, rapidly becoming a narco-state. But, as Strategic Trends 2011 points outs, ‘divergence’ throughout the international system may complicate the United States’ attempts to lead a coalition to break the narcotics-insecurity cycle.

Nov 26, 2011

Beginning with the 18th century, we have had a slew of thinkers who recurrently make “economic interdependence” arguments against war. One prominent example of this type of analyst was Sir Norman Angell, who later received the Noble Peace Prize for his anti-war work early in the 20th century. Prior to World War I, Angell published "The Great Illusion," which basically argued that the best way to discourage states from attacking each other was to so entangle their financial fates together that an attack by one against the other would constitute nothing less than economic suicide. More specifically, here's how Angell put it in the 1913 version of his famous text:

From a governance perspective, the management of multi-level complexity imparts considerable challenges. Overall, this period has dispersed power, most notably away from nation states. Embedded in a world complete with interdependencies, transnational phenomena and accelerated complexity, nation states have diminished capacity to mobilize and control physical (and virtual) borders, communication and financial systems, and the movement of goods and people. In sum, static, state-centric models of government are poorly equipped to handle this environment as they are predominantly inflexible – hindered by hierarchy and bureaucratic structures that limit the flow of information, engagement of multiple actors, and ability to change and adapt quickly.

In addition, system behavior is most troubling for the field of security if cascades and surprise effects are combined. Cascade effects are those that produce a chain of events that cross geography, time, and systems. Such effects are common in more interconnected, interdependent (referred to as tightly coupled) systems. Surprise effects are unexpected, but also truly unknowable events that arise out of interactions between agents and the negative and positive feedback loops produced through this interaction.

Using the complexity prism can help to understand the dynamics of today’s world which has become increasingly characterized by the non-linearity between cause and effect. Within the last 20 years alone, we have seen how globalization has brought online new relationships, influences, exchanges, and advances. Transformative changes in technology coupled with rampant growth in interconnectivity have created a world where societal and technical networks are continuously multiplying, increasing interactions across geographical space, time, and systems. With this, the role of non-state actors within the international system has grown markedly. This is evident when examining the proliferation and characteristics of dark networks.

Also, large systems with many components have the tendency to evolve into a poised and highly imbalanced “critical” state where minor disturbances may lead to events, called avalanches. This means that complex systems tend to adapt to, or are themselves on, the edge of chaos and most of the changes take place through catastrophic events rather than by following a smooth gradual path. The new path the system will take cannot be predicted and controlled before it is taken. Due to this emergent behavior, the complex system cannot be understood by reducing it to its parts; moreover, the behavior we are interested in evaporates when we try to reduce the system to a simpler, better-understood one.

Chaos and Complexity Studies

The precursor of complexity thinking is the investigation of dynamic systems. Very simply put, a system is a set of mutually dependent components or variables. Each component in the system stands in interrelation with every other component in the set and also in interaction with the system environment. In other words, the components interact with each other within the system’s boundaries to function as a whole to perform a task. Three types of systems exist:

- Ordered systems are those that are structured around a set of rules or laws that contain clear patterns where reliable outcomes can be determined. They are characterized by stability and discernible cause-and-effect relationships.

- Complex (adaptive) systems incorporate a number of variables that simultaneously play many different roles in the system’s evolution and following many different laws of behavior. These systems are non-linear and potentially volatile. Their behavior can only be discovered by studying how these elements interact and how the system adapts and changes throughout time.

- Chaotic systems are turbulent complex systems in transition to a different order. The relationships between cause and effect are impossible to determine because they shift constantly and no manageable patterns exist. No medium to long-term prediction whatsoever is possible.

The study of chaotic and complex systems has created a large and growing field of complexity science. While a variety of disciplines have used this analytical and theoretical prism, it has been particularly popular within the natural and, increasingly, social sciences. This trend points to the fact that complexity studies are applicable to all kinds of systems, regardless of their size or nature, like technological (sub-) systems, societal phenomena or the international political system.

In the post-Cold War era, stable and narrow security conceptions were broadened and deepened. Paralleled by discussions on moral necessities, western security policies were expanded to include political, societal, economic and environmental issues. As a result, the referent object of security was extended to groups, individuals, but also on inanimate objects such as technical infrastructure systems. At the same time, the notion of threat, understood as a problem that is deliberately created by one security actor for another, was losing saliency in many parts of the world. Several of the new challenges that security policy started to focus on in the post-Cold War world – global health issues, financial stability, critical infrastructure protection, but also terrorism to some extent – seemed much better captured by the concept of risk.

During the Cold War, the two superpowers combined geopolitical objectives with military capabilities that included weapons of mass destruction and the means to deliver them over intercontinental distances. Security threats were thus directly linked to military capabilities and arose mainly from the aggressive intentions of the other powerful actor in the international system. Although there were numerous strategic surprises during the Cold War, the ability to monitor each superpower’s strategic and military posture created a sense of certainty through calculability. To identify the level of threat, one looked at the capability of the enemy and their intent or motivation, in addition to one’s own vulnerability.

From a western perspective, there was not always agreement on the exact nature of the Soviet threat. The debate, however, evolved around the threat in terms of what could be measured; in other words, the threat in the form of actor, intention and capability was known or at least knowable. In addition, there was a belief that it was possible to defeat the threat and achieve security through known measures. The concept of deterrence in particular – which refers to the attempt to create risks so high in comparison to a possible gain that opponents refrain from engaging in a certain policy or action – existed as a credible option to prevent the threat from being enacted.

Using the controversy surrounding Iran's nuclear program as an example, this ISN multimedia feature illustrates how forecasts can be employed to serve the distinct interests of policymakers.

Despite forecasting’s dangers, however, the fact is that we now operate in a world defined by five domains (air, land, sea, space and cyberspace) and within a context defined by universal and instantaneous time. We therefore need all the “tilts” in the right directions we can get. We need to avoid being caught flat-footed. In other words, we need help not to react to events, but to anticipate and perhaps even shape them. International relations have always been complicated because of this desired shaping function. Well, that problem has only gotten worse over the last 20 years.

Recent academic research suggests that economists with a proven track record in predicting ‘extreme’ events like recessions actually have the worst overall forecasting reputation. But this problem is not unique to economists, of course. For example, Philip Tetlock, in his ‘Expert Political Judgment’, analyzed more than 80,000 political predictions made over two decades. As in the case of the economists, expert political opinion fared no better than chance did. That’s right, chance.

The Conference Board has just published its Global Economic Outlook 2012 report and it projects a 6.6 percent growth rate for China from 2013-2016 and then an average of 3.5 percent per year between 2017 and 2025. Aren’t these numbers, which are shared by others, a harbinger of a bumpy ‘road’ ahead if nothing else?

The 2010-2020 decade, for example, will see a reversal of the centuries-old trend of population growth driving economic relations. An ageing global population will strain, if not outright challenge, the economic structures and financial arrangements that have historically assumed that people would have shorter “non-productive” lives. The social and financial costs of this imbalance will have the most profound impact on the developed world as well as emerging countries like China and India. As a result, states will have to rely upon immigration from a new tranche of developing countries to compensate for irregularities and shortages in their labor markets.

The second road is a Multipolar World defined by a traditional order built around major nation-states. Nationalism once again exerts itself as a primal force in global affairs, with America and the West challenged by a rising Russia, Iran, India, Turkey and Brazil. This new multipolar arrangement would be global in scope and make for the empowerment of states long regarded by the West as barely capable of organizing themselves. New and improbable-sounding alliances would form -- between Russia and Turkey, and between Brazil and Iran, say. National 'spheres of influence' might have to be recognized, making life unhappy for the small nations of the planet. Should Europe recover its lost will to power, it could be a major player in such a world -- otherwise it risks being dominated by the others. As in the 19th century, peace in a multipolar world would hinge on a balance of power maintained by the biggest players at the point of a gun.

The third road is a Chinese Century. This would be proof of the proposition that the world, after all, does need a dominant player, a global rule maker, to ensure stability. If debt-ridden, imperially over-extended America can't do the job, then China, destined to become the world's largest economy, might have to step in. The world's clocks would be set on Beijing time; the yuan would supplant the dollar as the globe's reserve currency. America would be humbled but not necessarily miserable. The pragmatic Chinese aim mainly to enrich themselves, which augurs for the preservation of a global trading system in which the U.S. can participate.

The fifth road is a universal civilization leading to global government. The journey would be a creepy-crawl of an organic kind. The globalization of finance, already an economic reality, might lead naturally to a global financial sheriff. The globalization of ecological problems, like the warming of the planet, might lead to a global environmental regulator. A universal legal system might evolve to address matters like intellectual property rights. The new rulers of the world would be a global cosmopolitan elite -- the 'superclass' that now exists in embryonic form, gathering in places like Davos. Global government would be an invitation for utopian thinkers to impose their ideas on the planet -- but the superclass is actually a diverse one of contrasting ideologies. There might be two main parties -- a party of the grand planners, but also a party of market-oriented libertarian types, reflecting the division that now exists among globalists.

Nov 25, 2011

Arguments that support future forecasting can be separated into two distinct categories. First, such forecasting can represent a sincere attempt to anticipate conditions or events, and thereby not be caught “flat-footed” when they appear. Forecasting, in other words, attempts to think the unthinkable, prepare for the inevitable and control the controllable. Its utility is that it helps you rationalize and shape political strategies, as well as articulate and integrate these strategies into effective policies. Second, future forecasting can also serve educational, polemical, propagandistic or ideological ends. Now, instrumentalizing forecasting in this way can obviously have positive and negative consequences. On the positive side, forecasters can use their prognostications to publicize what they think are underappreciated dangers or potential threats. They can, in short, use their forecasts to educate others and better shape their expectations of future developments. On the more dubious side, those who practice future forecasting can tailor their predictions to ‘label’ threats and risks, for example, to promote more private interests and agendas.

Nov 22, 2011

These changes, of course, don’t remove the CIA from the assassination business or establish a definitive end date for the drone war. But the logic of drone technology – and its rapid proliferation – will soon prompt a more radical rethink. After all, the Pentagon wanted the United States to abide by the Geneva Conventions not because of a sudden conversion to human rights advocacy, but because of a fear of what other countries might do to U.S. soldiers. And U.S. officials eventually came to understand the usefulness of arms control not out of a commitment to world peace, but because the Soviet Union had acquired a sizable and quite dangerous arsenal of its own.

Today, the United States maintains a near monopoly on military drone technology, with only Israel and Britain also deploying these systems. But the landscape is rapidly changing. As David Cortright at the University of Notre Dame points out, more than 50 countries are developing or buying drone systems, including China and Iran, and even non-state actors want in on the business. The United States is now using drones to patrol borders and collect information about Mexican narcotraffickers. U.S. law enforcement agencies are also eager to use the technology against criminals on U.S. soil, withTexas sheriffs leading the way. Unmanned drones are already used in Japan, Australia, and other countries for such civilian activities as crop dusting and lifeguarding.

Nov 21, 2011

The End of Population Growth - (Nation of Change - October 31, 2011)

"[I]t is likely that world population will peak at nine billion in the 2050's, a half-century sooner than generally anticipated, followed by a sharp decline." Most countries conducted their national population census last year, and the data suggest that fertility rates are plunging in most of them. Birth rates have been low in developed countries for some time, but now they are falling rapidly in the majority of developing countries. Chinese, Russians, and Brazilians are no longer replacing themselves, while Indians are having far fewer children. Indeed, global fertility will fall to the replacement rate in a little more than a decade. Population may keep growing until mid-century, owing to rising longevity, but, reproductively speaking, our species should no longer be expanding.

Nov 20, 2011

Nov 18, 2011

This is a problem for everyone, rich and poor, because international evidence suggests that more equal economies grow faster. In fact, the historical evidence for the Americas, compiled in 2005 by economists Stanley Engerman and the late Kenneth Sokoloff of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) suggests that an early source of wealth in the American Northeast was a colonial farming system based around small landholders that encouraged equality and the provision of public goods -- as opposed to the plantation model used in the South and the Caribbean, which favored a small elite uninterested in representative government or widespread education.

The top fifth of households in the United States earn 10 times what the poorest fifth makes and more than the rest of the country combined. The incomes of the richest 1 percent are 67 times those of the poorest 20 percent of households. And over time, that gap has widened. According to theCongressional Budget Office, between 1979 and 2007, the richest 1 percent saw their after-tax incomes climb 275 percent compared with an 18 percent rise for the poorest fifth. The story is similar, if less dramatic, in other rich economies.

Nov 17, 2011

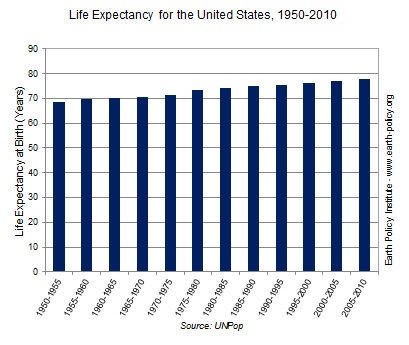

Some high-income countries are improving life expectancy but failing to keep pace with their peers. For example, since 1980 the United States has only extended its average expected lifespan by 4 years, while Japan—the country where people can expect to live the longest, to age 83—has increased it by 6 years. A 2011 study from the University of Washington found that in addition to lagging behind leading countries, the United States has significant geographic and racial disparities in life expectancy.

Studies suggest that the slower U.S. rate of improvement may be a legacy of heavy smoking—historically more common in the United States than in Japan and many European countries—as well as of obesity and a lack of universal health care.

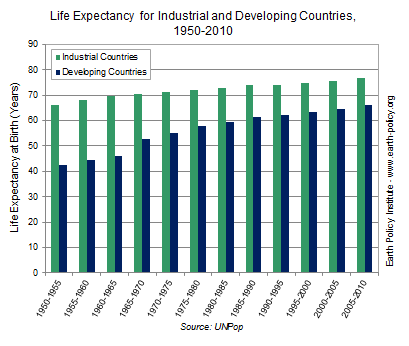

People born today will live for 68 years on average, 20 years longer than those born in 1950. By the mid-twentieth century, industrial countries had already made major strides in extending lifespans with improvements in sanitation, nutrition, and public health. After World War II, rapid gains in life expectancy in developing countries began to narrow the gap between these nations and industrial countries. Although average life expectancy worldwide continues to increase, gains have come more slowly in the last few decades. Worryingly, life expectancy has actually declined in some developing countries, while a few industrial countries have stalled or made slow progress on this important indicator of human health and well-being.

Nov 15, 2011

The threat of government default and the prospect of economic austerity are bad enough. The political fallout might be even worse. Europe has been overwhelmed by a rising tide of extreme nationalism. Far right-wing parties have been gaining strength throughout the continent, particularly in places that have been largely immune to such extremism in the last 50 years. The Progress Party in Norway, to which mass murderer Anders Breivik was once affiliated, is now the second-largest party there; Geert Wilders, the flamboyant Islamophobe of the Netherlands, has led his party into third place; the Democratic Party in Sweden, which similarly focuses its wrath on immigrants, made it into parliament for the first time in the 2010 elections.

These extremist successes in the putative territories of tolerance augment the rising support for far-right wing parties elsewhere in Europe — Jobbik in Hungary, the Northern League in Italy, the Freedom Party in Austria. Ultra-nationalists have also been effective at organizing on a local level. The far-right-wing Plataforma per Catalunya is making headway in municipalities across the Catalan region of Spain. In Athens, a neo-Nazi recently won a spot on the city council. And these are the polite ones. Right-wing vigilantes have rampaged on the streets of Sofia, Gyöngyöspata, Dudley, Warsaw, and other places.

From a thug's eye view, Europe today looks a lot like Europe of the 1930s: steeped in economic crisis and cursed by dithering politicians, with Islamophobia and anti-Roma sentiment substituting for anti-Semitism. Then as now, the far right has employed a dangerous populism to take advantage of the economic downturn. It has identified two primary culprits — immigrants (who compete for jobs and government benefits) and European institutions (which mismanaged the economic situation)

09 November 2011 London --- Without a bold change of policy direction, the world will lock itself into an insecure, inefficient and high-carbon energy system, the International Energy Agency warned as it launched the 2011 edition of the World Energy Outlook (WEO). The agency's flagship publication, released today in London, said there is still time to act, but the window of opportunity is closing.

"Growth, prosperity and rising population will inevitably push up energy needs over the coming decades. But we cannot continue to rely on insecure and environmentally unsustainable uses of energy," said IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven. "Governments need to introduce stronger measures to drive investment in efficient and low-carbon technologies. The Fukushima nuclear accident, the turmoil in parts of the Middle East and North Africa and a sharp rebound in energy demand in 2010 which pushed CO2 emissions to a record high, highlight the urgency and the scale of the challenge."

Nov 14, 2011

World Energy Outlook 2011

November 14, 2011 by Editor

Global installed power generation capacity and additions by technology in the New Policies Scenario (credit: IEA)

Without a bold change of policy direction, the world will lock itself into an insecure, inefficient and high-carbon energy system, the International Energy Agency warned in the 2011 edition of the World Energy Outlook (WEO).

- The average oil price remains high, approaching $120/barrel (in year-2010 dollars) in 2035.

- Oil demand rises from 87 million barrels per day (mb/d) in 2010 to 99 mb/d in 2035, with all the net growth coming from the transport sector in emerging economies.

- With oil production declining in all existing fields, an increasing share of liquid fuels will come from natural gas liquids and oil sands, with Russia’s role as a supplier of natural gas more pivotal.

- In the WEO’s central New Policies Scenario, which assumes that recent government commitments are implemented in a cautious manner, primary energy demand increases by one-third between 2010 and 2035, with 90% of the growth in non-OECD economies.

Nov 9, 2011

Artificially intelligent entities will evolve faster and farther than humans. While natural human evolution has slowed, technological evolution is accelerating. Humans may increasingly adapt themselves with technological enhancements in order to keep up the pace. —Steven M. Shaker, “The Coming Robot Evolution Race,” Sep-Oct 2011, p. 20

China’s economy will stop growing and start shrinking later this century. So forecasts economist Daniel Altman, who notes that China is an economic powerhouse now, but structural weaknesses threaten to cause major problems in the long term. Meanwhile, prosperity will resume in the United States and a few other nations that are now lagging. —Books in Brief [review of Outrageous Fortunes by Daniel Altman], Jan-Feb 2011, p. 48

The U.S. rich–poor gap is another disaster waiting to happen—probably around 2020. If the economic situation looks bad now, just wait until the end of the decade. Present-day concentration of wealth in the hands of too few Americans, and the related problem of out-of-control consumer debt, will lead to economic stagnation and political upheaval with impacts felt across the world.

Nov 8, 2011

The fundamental patterns of European domination held for 500 years. That epoch of history ended in 1991, when the Soviet Union — the last of the great European empires — collapsed with global consequences. In China, Tiananmen Square defined China for a generation. China would continue its process of economic development, but the Chinese Communist Party would remain the dominant force. Japan experienced an economic crisis that ended its period of rapid growth and made the world’s second-largest economy far less dynamic than before. And in 1993, the Maastricht Treaty came into force, creating the contemporary European Union and holding open the possibility of a so-called United States of Europe that could counterbalance the United States of America.

Change in the international system comes in large and small doses, but fundamental patterns generally stay consistent. From 1500 to 1991, for example, European global hegemony constituted the world’s operating principle. Within this overarching framework, however, the international system regularly reshuffles the deck in demoting and promoting powers, fragmenting some and empowering others, and so on. Sometimes this happens because of war, and sometimes because of economic and political forces. While the basic structure of the world stays intact, the precise way it works changes.