Solar Power 2011 - Solar PV Breaks Records in 2010 | |||

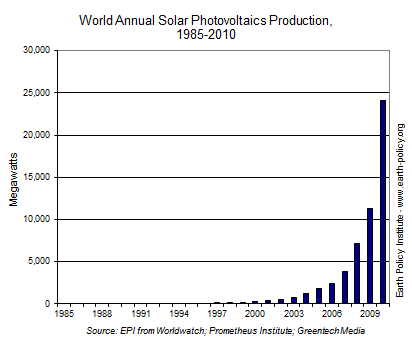

Solar photovoltaic (PV) companies manufactured a record 24,000 megawatts of PV cells worldwide in 2010, more than doubling their 2009 output. Annual PV production has grown nearly 100-fold since 2000, when just 277 megawatts of cells were made. Newly installed PV also set a record in 2010, as 16,600 megawatts were installed in more than 100 countries. This brought the total worldwide capacity of solar PV to nearly 40,000 megawatts—enough to power 14 million European homes. | |||

Oct 27, 2011

Oct 26, 2011

A diverse portfolio of energy technologies will replace our reliance on fossil fuels. Scientists are exploring not just wind and solar energies, but also such esoteric technologies as artificial photosynthesis, traveling wave reactors, and mini black holes. —David J. LePoire, “Exploring New Energy Alternatives,” Sep-Oct 2011, pp. 34-38

Artificially intelligent entities will evolve faster and farther than humans. While natural human evolution has slowed, technological evolution is accelerating. Humans may increasingly adapt themselves with technological enhancements in order to keep up the pace. —Steven M. Shaker, “The Coming Robot Evolution Race,” Sep-Oct 2011, p. 20

The Internet will automatically search itself so you don’t have to. The information you provide Google when you search for something is teaching the search engine more about you and your interests. One day, Google will become so savvy about you that you won’t have to search at all: Your smartphone will pick up information from your environment, anticipate what you’ll want to know, and deliver it automatically. At least, that is the hope of Google developers. Privacy advocates such as Eli Pariser, author of The Filter Bubble, warn of abuses by companies that could profit from such private information. —Eli Pariser, “The Troubling Future of Internet Search,” World Trends & Forecasts, Sep-Oct 2011, p. 6

Oct 25, 2011

The United States and the rest of the world have, of course, lived through profound technological and employment shifts in the past. As Byrnjolfsson points out, about 90 percent of Americans worked on farms in 1800, but by 1900, that number was only 41 percent, thanks partly to technology and partly to the opening of more-fertile farmland in the Midwest. Yet people adapted and new jobs emerged. "We have always had to redeploy and reinvent," he says, "but now it's happening so fast that people aren't keeping up."

Oct 24, 2011

There have been 165 wars or tyrannies of the 20th Century which have killed more than 6,000 people. Five of these events claimed more than 6 million victims. Twenty-one events claimed between 600,000 and 6 million lives. Sixty-one events claimed between 60 and 600 thousand, and seventy-eight events killed between 6 and 60 thousand.

Well, what can you say about a century that begins and ends with killing in Sarajevo? "Good riddance" springs to mind. Somewhere around 180 million people have been killed in one Twentieth Century atrocity or another -- a far larger total than for any other century in human history.

We’ve all had the experience of reading about a bloody war or shocking crime and asking, “What is the world coming to?” But we seldom ask, “How bad was the world in the past?” In this startling new book, the bestselling cognitive scientist Steven Pinker shows that the world of the past was much worse. With the help of more than a hundred graphs and maps, Pinker presents some astonishing numbers. Tribal warfare was nine times as deadly as war and genocide in the 20th century. The murder rate of Medieval Europe was more than thirty times what it is today. Slavery, sadistic punishments, and frivolous executions were unexceptionable features of life for millennia, then suddenly were targeted for abolition. Wars between developed countries have vanished, and even in the developing world, wars kill a fraction of the people they did a few decades ago. Rape, battering, hate crimes, deadly riots, child abuse, cruelty to animals—all substantially down.

How could this have happened, if human nature has not changed? What led people to stop sacrificing children, stabbing each other at the dinner table, or burning cats and disemboweling criminals as forms of popular entertainment? The key to explaining the decline of violence, Pinker argues, is to understand the inner demons that incline us toward violence (such as revenge, sadism, and tribalism) and the better angels that steer us away. Thanks to the spread of government, literacy, trade, and cosmopolitanism, we increasingly control our impulses, empathize with others, bargain rather than plunder, debunk toxic ideologies, and deploy our powers of reason to reduce the temptations of violence.

How do you explain the decline in violence?

I don't think there is a single answer. One cause is government, that is, third-party dispute resolution: courts and police with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Everywhere you look for comparisons of life under anarchy and life under government, life under government is less violent. The evidence includes transitions such as the European homicide decline since the Middle Ages, which coincided with the expansion and consolidation of kingdoms; the transition from tribal anarchy to the first states. Watching the movie in reverse, in today's failed states violence goes through the roof.

I was struck by a graph I saw of homicide rates in British towns and cities going back to the 14th century. The rates had plummeted by between 30 and 100-fold. That stuck with me, because you tend to have an image of medieval times with happy peasants coexisting in close-knit communities, whereas we think of the present as filled with school shootings and mugging and terrorist attacks.

Then in Lawrence Keeley's 1996 book War Before Civilization I read that modern states at their worst, such as Germany in the 20th century or France in the 19th century, had rates of death in warfare that were dwarfed by those of hunter-gatherer and hunter-horticultural societies. That too, is of profound significance in terms of our understanding of the costs and benefits of civilisation.

Throughout much of this century the notion has been gaining ground, bolstered by genocide and Holocaust, that modern warfare is more barbaric than war has ever been. Alongside this view has grown a romantic impression that primitive cultures were, and are, more peaceful. Lawrence Keeley, an anthropologist at the University of Illinois, aims to dispel this inversion of the connotations of "civilization." He cites the historical evidence that humans have always been just as bloodthirsty as they are today, and that indeed in the days when death was less clinical it was often nastier. War, it seems, has always been with us. -

Oct 20, 2011

The conditions making for external intervention in Africa are growing, not diminishing. The continent is today the site of a growing contention between dominant global powers and new challengers. The Chinese role on the continent has grown dramatically. Whether in Sudan and Zimbawe, or in Ethiopia, Kenya and Nigeria, that role is primarily economic, focused on two main activities: building infrastructure and extracting raw materials. For its part, the Indian state is content to support Indian mega-corporations; it has yet to develop a coherent state strategy. But the Indian focus too is mainly economic.

Bioviolence Becomes a Greater Threat—In the next decade, biological technologies that were once at the frontiers of science will become available to anyone with minimal scientific training. Emerging biotechnologies, such as genomics and nanotechnology, will allow bacteria and viruses to be altered to increase their lethality or make them more resistant to antibiotics.

Oct 19, 2011

Now, there is a new trend that is rapidly proliferating across the world: unhappiness with leadership. It's as though the uprisings of northern Africa, focused on very specific, authoritarian leaders, has turned into broad-based global demonstrations against leadership, in places where it was never previously thought possible.

I was with a retired army colonel recently who mentioned that throughout his career he had many times told friends from other countries where he had served that the American people would never revolt against their government. He doesn't know about that now. He was responding to the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations, now more than a month long that have spread to 30 U.S. cities and drew 20,000 participants in New York a week ago.

In preparing for a talk that I will give later this week in Santiago, Chile, I discovered that United for Global Change -- the central site for the movement organizing worldwide protests -- said 951 cities in 82 countries were to take part in the demonstrations after online organizers called for a worldwide rally. This is particularly of interest to the Chileans I will be visiting since their students have been on strike for many months now calling for free education (they'll lose one year of school because of their commitment). One of my talks at a university was cancelled because of massive, city-wide demonstrations that are planned to take place while I will be there.

What's interesting about this growing trend of broad-based discontentment with the status quo is that it is moving into the middle and upper classes. In the U.S., for example, when mainline commentators like Suze Orman start to endorse the concerns of demonstrators and magazines like The New Yorker publish covers like this, then you know that a very sensitive nerve has been touched by those mostly young people who are camping in the rain to try to influence significant change.

An even more interesting data point is when Warren Buffett, one of the wealthiest men in America chimed in to suggest that the constitution needs to be changed to make it impossible to allow all politicians to run for reelection if the national debt exceeds 3% of the present ceiling. Now, that would certainly get their attention!

Oct 18, 2011

Friedman and Mandelbaum describe the US Congress as "increasingly beholden to the wealthiest and most politically extreme interests in America" and the political system in general as "under the sway of powerful special interests that work for policies that are at best irrelevant to and at worst counterproductive for the urgent present and future needs of the United States".

Oct 17, 2011

Much of this Web site examines the performance of the U.S. economy over time—using historical outcomes as a benchmark. This section instead compares the United States across space—benchmarking its performance to its global peers, the 19 other richest industrialized countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The comparison thus provides an alternative yardstick to gauge the strengths and weaknesses of the U.S. economy.

Oct 13, 2011

No wonder Jim O’Neill, who coined the neologism BRIC and is now chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management, has been stressing that “the world is no longer dependent on the leadership of the U.S. and Europe.” After all, since 2007, China’s economy has grown by 45%, the American economy by less than 1% -- figures startling enough to make anyone take back their predictions. American anxiety and puzzlement reached new heights when the latest International Monetary Fund projections indicated that, at least by certain measurements, the Chinese economy would overtake the U.S. by 2016. (Until recently, Goldman Sachs was pointing towards 2050 for that first-place exchange.)

Within the next 30 years, the top five will, according to Goldman Sachs, likely be China, the U.S., India, Brazil, and Mexico. Western Europe? Bye-bye!

Oct 12, 2011

Earth Policy Release | |||

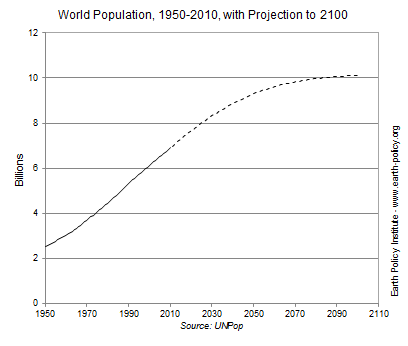

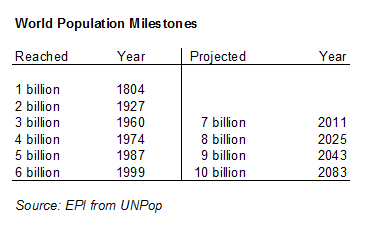

The number of people in the world is expected to reach 7 billion by the end of October 2011. Our rate of increase continues to slow from the high point of over 2 percent in 1968. Still, this year's 1.1 percent increase means some 78 million people will be added to the global population in 2011. With populations stabilizing in much of the industrial world, almost all population growth in the near future is expected to occur in developing countries. Of the 2.3 billion people to be added by 2050, more than a billion will live in sub-Saharan Africa. The Indian subcontinent will add some 630 million people. Differences in population growth rates are largely due to varying fertility levels. Global fertility has dropped from close to 5 births per woman in the 1950s to 2.5 births per woman today. Over 40 percent of the world's people live in countries where fertility is below replacement level. But fertility varies widely across countries. In Niger, women have more than 7 children on average; in the United States the average is close to 2, and in Japan it is less than 1.5. | |||

Oct 7, 2011

The U.S. economy appears to be coming apart at the seams. Unemployment remains at nearly ten percent, the highest level in almost 30 years; foreclosures have forced millions of Americans out of their homes; and real incomes have fallen faster and further than at any time since the Great Depression. Many of those laid off fear that the jobs they have lost -- the secure, often unionized, industrial jobs that provided wealth, security, and opportunity -- will never return. They are probably right...

And yet a curious thing has happened in the midst of all this misery. The wealthiest Americans, among them presumably the very titans of global finance whose misadventures brought about the financial meltdown, got richer. And not just a little bit richer; a lot richer. In 2009, the average income of the top five percent of earners went up, while on average everyone else's income went down. This was not an anomaly but rather a continuation of a 40-year trend of ballooning incomes at the very top and stagnant incomes in the middle and at the bottom. The share of total income going to the top one percent has increased from roughly eight percent in the 1960s to more than 20 percent today...

The dramatic growth of inequality, then, is the result not of the "natural" workings of the market but of four decades' worth of deliberate political choices. Hacker and Pierson amass a great deal of evidence for this proposition, which leads them to the crux of their argument: that not just the U.S. economy but also the entire U.S. political system has devolved into a winner-take-all sport. They portray American politics not as a democratic game of majority rule but rather as a field of "organized combat" -- a struggle to the death among competing organized groups seeking to influence the policymaking process. Moreover, they suggest, business and the wealthy have all but vanquished the middle class and have thus been able to dominate policymaking for the better part of 40 years with little opposition.

Oct 6, 2011

| Transferring Cost of War to Latin America is Morally, Politically Wrong |

| The US has begun recruiting contractors for Latin American countries to carry out security tasks in its war zones in an effort to minimize US causalities and prevent domestic opposition to the US's many military interventions abroad. Though the US argues that economically this arrangement benefits both the US and the Latin American contractors, it is morally and politically unacceptable to pay foreigners to "take risks for us" in order to avoid paying the "political cost" of waging otherwise unpopular wars. (Common Dreams) |

Oct 4, 2011

Could software-based mediation spread from divorce settlements and utility pricing to resolving political and military disputes? Game theorists, who consider all these to be variations of the same kind of problem, have developed an intriguing conceptual model of war. The “principle of convergence”, as it is known, holds that armed conflict is, in essence, an information-gathering exercise. Belligerents fight to determine the military strength and political resolve of their opponents; when all sides have “converged” on accurate and identical assessments, a surrender or peace deal can be hammered out. Each belligerent has a strong motivation to hit the enemy hard to show that it values victory very highly. Such a model might be said to reflect poorly on human nature. But some game theorists believe that the model could be harnessed to make diplomatic negotiations a more viable substitute for armed conflict.