Natural intelligence evolution starts from wormlike animals with a few hundred neurons occurring more than 570 million years ago. Very primitive fish that appeared 470 million years ago had about 100,000 neurons. One hundred million years later, amphibians with a few million neurons emerged from the swamps. One hundred fifty million years later, the first small mammals appeared and had brain capacities with several hundred million neurons. The bigger co-inhabitants at the time, the dinosaurs, had brains with several billion neurons.…

Aug 24, 2011

This principle draws a distinction between futuring and visioning. Futuring looks at what is most plausibly, even likely, to unfold, given trends, evolving conditions, and potentially disruptive changes. It emphasizes conditions that are partially if not largely out of your own control. Visioning, on the other hand, involves formulating aspirational views of the future based on what you want to see happen—in other words, how you would like events to play out. Of course, just because you want a certain future to happen does not guarantee that it will. Strategic planning is a manifestation of visioning. If an organization does not engage in forecasting with all the rigor of historical criticism and good science, strategic planning can be just so much wishful thinking. I find that wishful thinking is alive and well in many corporations and institutions. Both futuring and visioning are necessary and they go hand-in-hand—just be careful to correctly identify which you are doing and why.

Thus, the future always has been and most likely always will be an unknown combination of both trend continuities and discontinuities. Figuring out the precise combination is extremely difficult. Therefore, we must study the trends but not blindly project them into the future—we have to consider historical trends, present conditions, and imagined changes, both great and small, over time. You might say that trend analysis is “necessary but not sufficient” for futuring; the same goes for imagined changes, too.

Futuring is an example of what I call “applied history,” or the use of historical knowledge and methods to solve problems in the present. It addresses the question “What happened and why?” in order to help answer the question “How might things be in the future and what are the potential implications?” Futuring, at least in a management context, combines applied history with other methods adapted from science, mathematics, and systems analysis to frame well-considered expectations for the future. This process will help us to make decisions in the present that will have positive long-term consequences

As The Economist reports this week, many women in the richer parts of Asia have gone on “marriage strike”, preferring the single life to the marital yoke. That is one reason why their fertility rates have fallen. And they are not alone. In 83 countries and territories around the world, according to the United Nations, women will not have enough daughters to replace themselves, unless fertility rates rise. In Hong Kong, for example, a cohort of 1,000 women would be expected to give birth to just 547 daughters, at today’s fertility rates. (That gives Hong Kong a “net reproduction rate” of just 0.547, in the language of demographers.) If nothing changed, those 547 daughters would be succeeded by just 299 daughters of their own, and so on. At that rate, according to some back-of-the-envelope calculations by The Economist, it would take about 25 generations for Hong Kong’s female population to shrink from 3.75m to just one. Given that Hong Kong’s average age of childbearing is 31.4 years, it could expect to give birth to its last woman in the year 2798. (That is some time after its neighbour, Macau, which has a higher reproduction rate, but a much smaller population.) By the same unflinching logic, Japan, Germany, Russia, Italy and Spain will not see out the next millennium. Even China, which has a recorded history stretching back at least 3,700 years, has only about 1,500 years left—if present trends continued unbroken.

Aug 18, 2011

We can look forward to bigger and more frequent financial catastrophes as well. Think of equity capital as land, industry segment as location, and financial risk as density. Concentrating all of these means greater productivity, but it also means that we are inviting ever more catastrophic financial hurricanes. How could the defaulted home loan of a strawberry picker in California wipe out $16 trillion in global financial market value and put so many people out of a job?

As the World Bank observed in its 2009 World Development Report, half the world's GDP is produced on 1.5 percent of its land surface. Humanity's global migration toward ever denser urban living has added trillions of dollars to the global GDP every decade since at least the end of World War II.

Just as the mechanical innovations of the 19th century led to dramatic changes in our way of life, the still-evolving computing and communication innovations of the early 21st century will have a profound impact on the world's economy and culture. For example, even the smallest company can now afford a communications and computational infrastructure that would have been the envy of a large corporation 15 years ago. If the late 20th century was the age of the multinational company, the early 21st will be the age of the micromultinational: small companies that operate globally.

The Future Is Now

Aug 13, 2011

The financial and economic crises have not only been a defining trend in international affairs, but together have acted as catalysts for both geoeconomic and geopolitical shifts that were already underway from West to East. If the US currently spends more than six times as much as China on defense, this equation is changing as a decade of modernization of China’s military is beginning to bear fruit, especially in terms of its expanding naval capabilities that allow it to gain a stronger hand in the Asia-Pacific. Other emerging markets will look to play a greater role to reflect growing economic ambitions. Europe is slowly waking up to the fact that a useful barometer for its own political clout has to be set against US-Asia relations. This plenary session discusses the implications of these developments for international security: How stable is the emerging multipolar international system? How will global governance play out in the future? Are the BRICS countries as cohesive as the acronym suggests? Will the US be able or willing to underwrite global security indefinitely? And what are the implications for American statecraft?![]() Listen to Closing Plenary Session (Audio)

Listen to Closing Plenary Session (Audio)

Aug 4, 2011

Humans have been co-evolving with their technologies since the dawn of prehistory, when tool making and meat eating co-evolved with brain development and social complexity. What is different now is that we have moved beyond external technological interventions to transform ourselves from the inside out—even as we also remake the Earth system itself. Coping with this new reality, say Allenby and Sarewitz, means liberating ourselves from such categories as "human," "technological," and "natural" to embrace a new techno-human relationship. Describing the- terms of this relationship, and exploring sociotechnical systems ranging from railroads to modern military technology, Allenby and Sarewitz ultimately locate individual authenticity in the quest for a new humility in the face of the rapidly disappearing moorings of the Enlightenment.

Aug 1, 2011

It also alerts readers to major changes that seem inevitable. For example, the coming biological revolution may change civilization more profoundly than did the industrial or information revolutions. The world has not come to grips with the implications of writing genetic code to create new lifeforms. Thirteen years ago, the concept of being dependent on Google searches was unknown to the world; today we consider it quite normal. Thirteen years from today, the concept of being dependent on synthetic life forms for medicine, food, water, and energy could also be quite normal.

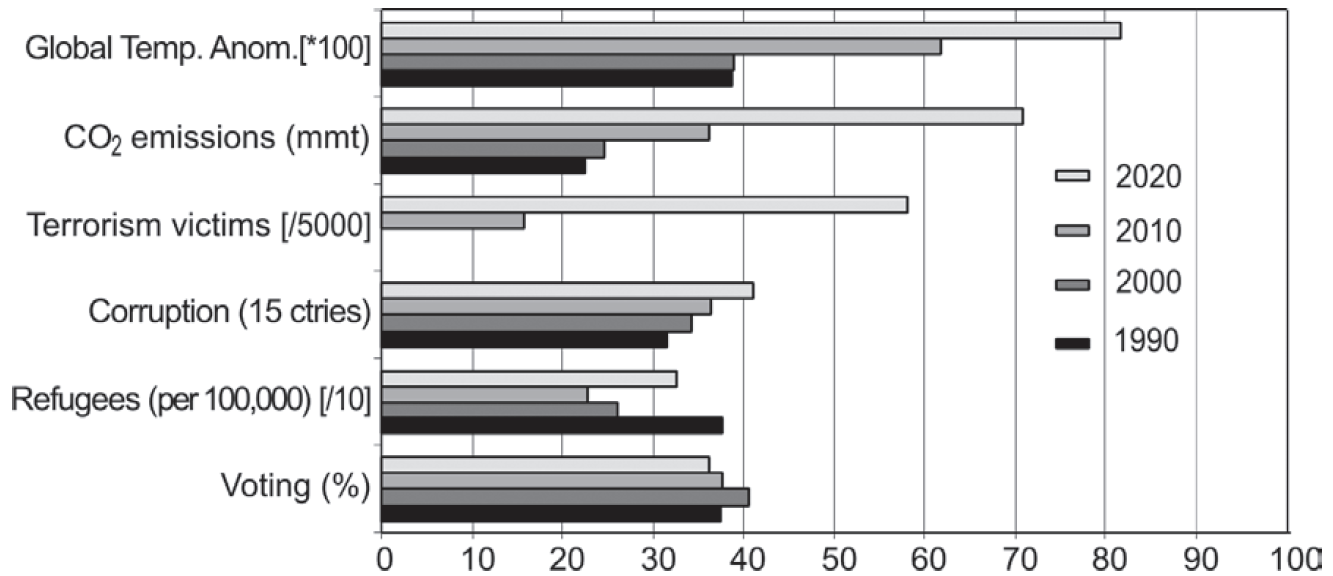

The Millennium Project’s 2011 State of the Future Report, due out August 1, finds that while people are getting richer, healthier, better educated, and living longer, and the world is more peaceful and better connected, half of the world is potentially unstable. “Food prices are rising, water tables are falling, corruption and organized crime is increasing, environmental viability for life support is diminishing, debt and economic insecurity are increasing, climate change continues, and the gap between the rich and poor is widening dangerously,” the report says. “People voting in elections, corruption, people killed or injured in terrorist attacks, and refugees and displaced persons are also identified as key problems. “The world is in a race between implementing ever-increasing ways to improve the human condition and the seemingly ever-increasing complexity and scale of global problems.”